Submarines, space and Shannon – Repurposing the birthplace of duty free for the 21st century

As guardian to much of western Europe’s technology infrastructure, the responsibilities Ireland faces in a digital economy are ever increasing. Recent incursions by Russian communications and reconnaissance aircraft into the North Atlantic have shown that the country is not sufficiently prepared to deal with this threat. At the same time, Shannon Airport’s importance as a passenger gateway has been declining ever since the 1960s. An opportunity now exists to leverage the airport’s geographic location once again and bring Ireland’s defence capabilities into the modern era.

Threat from the East

In a near repeat of several incidents this year, RAF Typhoons from Leuchars in Scotland were last weekend dispatched to intercept two Russian Tu-142 Bear ‘F’ aircraft approaching the UK’s “area of interest”, a swathe of territory in the North Atlantic covering the waters north and west of Scotland and those west of Ireland. While the RAF’s response was co-ordinated from the NATO Combined Air Operation Centre in Germany, the aircraft were tracked by operators at RAF Boulmer in Northumberland and overseen by the UK’s National Air and Space Operations Centre in High Wycombe. A complex but well-coordinated, and now well-rehearsed, operation.

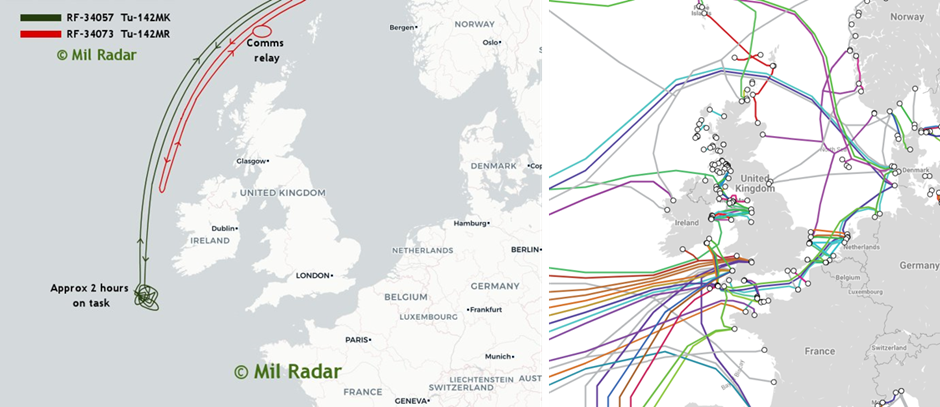

The appearance of the Bear ‘F’ is significant in that it represents Russia’s submarine warfare variant of the venerable Tu-95 bomber and an aircraft which performs a function similar to the RAF’s Boeing P8 Poseidon. In a March incident, the Bears transited north-south along the oceanic entry points for commercial air traffic west of Ireland, spending approximately two hours on task off the coast of Cork before returning along the same path. While undoubtedly a test of the RAF’s capability to respond to such incidents, one might ask what the Irish response was to this? Simply put, there was none, and no capability exists.

As home to a broad range of technology companies, pharmaceutical manufacturers and data centres, Ireland sits as gate keeper for much of Europe’s communications links to North America. A look at the ground track of the March Bear ‘F’ incursion and the location of transatlantic fibre optic cables need not require a military strategist to understand the threat. With the Irish Air Corps unable to undertake any aerial intercept function and the Irish Navy primarily engaged in fisheries patrol or narcotics enforcement, submarines are by and large free to engage in nefarious activities in Irish territorial waters.

The Shannon Question

Stepping out of the military context for a moment, COVID-19 is having an extraordinary impact on Irish regional airports and once again the question of Shannon has come into focus. With news that Aer Lingus is likely to transfer transatlantic flights from the airport to UK regional cities – Manchester and Edinburgh being likely contenders – and Ryanair threatening to close its base, it calls into question the viability of the airport’s passenger operations. Once a thriving location for North Atlantic stopovers, and an airport that brought the world duty free, Shannon’s importance has been in decline since the 1960’s advent of jet transportation.

Nonetheless, the airport continued to attract airlines, courting American carriers such as Delta in the 1980s and ongoing operations from Aer Lingus – aided of course by the government’s regulations dictating Shannon as a compulsory transatlantic gateway to Ireland. While 747s and Tri-stars in the eighties gave way to A330s and 767s in the nineties and noughties, in recent years seasonal 757 operations became the norm; these services most recently transitioning to the A321LR. Local politicians continuously tout the region’s direct links with the United States and Heathrow as vital to the mid-west’s economy, but airlines are clearly voting with their feet. More profitable routes exist elsewhere.

All of this is not to say Shannon serves no function – quite the opposite. With its long runway and geographical location, it remains a crucial emergency diversionary airfield for civilian airliners and remains home to substantive heavy maintenance facilities. Its surrounding waters also served as an abort zone for May’s launch of the SpaceX Crew Dragon while it was once listed as an emergency landing facility for the Space Shuttle. The airport is also a key staging point for the Irish Coast Guard’s search and rescue operations. Simply put, Shannon needs to exploit its geographic location once again, but it requires imagination and political will to see past its current purpose as a passenger facility. Herein lies the opportunity to both revitalise Shannon and simultaneously bring Ireland’s defence capabilities into the 21st century.

Military & Space Realignment

The proposition – relocate the Irish Air Corps’ fixed wing capability to the west of Ireland. The existing infrastructure at Shannon and its geographical location makes it ideally suited to North Atlantic operations. Maritime patrol and search and rescue activities could be collocated and the much talked about lack of Irish military air lift capacity might be solved with the purchase of even a single Airbus A400M aircraft (much as Luxembourg has done) based at the airport. With the capability to transport troops, equipment, VIPs and conduct air to air refuelling with rotary wing assets, the A400M could play a significant part in long range search and rescue as well as United Nations peacekeeping obligations. A squadron of fast jets would offer the much needed QRA (Quick Reaction Alert) function while the on-order Airbus CN295 maritime patrol aircraft would now be optimally positioned.

Apart from retaining its baseline passenger operations alongside a proposed military presence, the burgeoning horizontal space launch industry is also in need of facilities from which to stage operations. Newquay Airport in Cornwall is already touting its spaceport credentials with Virgin Orbit as its first customer. And though Ireland is not ideally suited to easterly land-based launches, the North Atlantic provides several options to avail of polar orbits (both north and south) from rockets carried by a host aircraft. The infrastructure for such a capability is not overly complex and is certainly not something Shannon is incapable of providing. With well-established standards developed by the FAA governing space launches available and the UK having released their own for public consultation, there is a wealth of existing information to build upon.

Defence as an Industry

Nevertheless, defence and defence procurement are somewhat of a political sensitivity in a country still officially neutral. But the proposal here involves seeing defence in a much broader perspective – Ireland’s responsibilities to safeguard communications infrastructure, and the potential such a capability might bring in creating a thriving defence sector with a highly skilled workforce. A look at our neighbours in the UK and Europe can give the country a glimpse as to how this works in practice, particularly in challenging times.

In Scotland, RAF Lossiemouth is currently undergoing significant modernisation to accommodate the P8 Poseidon safeguarding construction, engineering, and local employment in Moray for decades to come. The UK defence sector as a whole has continued to support highly skilled jobs throughout the COVID-19 crisis stemming an otherwise steady flow of skilled individuals from the private sector. Across Europe, defence procurement continues unabated with the first sod turned at the future home of Denmark’s F35s and similar projects in the pipeline for both Poland and Belgium. All these examples are merely scratching the surface of a more significant capability encompassing cyber security, signals intelligence and maritime surveillance amongst others.

The narrative here is quite simple. Reinvigorating the Irish Defence Forces, and properly equipping it to deal with the threats of the 21st century, has the potential to revitalise the west of Ireland and with it the Shannon region. It would allow the country to strengthen its position as a secure technology hub and deepen cooperation with a post-Brexit UK and our European partners. But while the narrative might be simple, political will is not.

Posted: 2020-09-15 at 20:42 GMT