The rise of the A321 as a long-haul airliner and the potential hidden infrastructure costs for airport operators

In the years since the arrival of the 747 into commercial passenger service in 1970, long-haul air travel has evolved from being a privilege of the wealthy to a price point less than that of your annual car service. The "Jumbo Jet" became synonymous with mass air travel and affordability and to this day is seen as a symbol of international connectivity. But times have changed and so have the aircraft of choice.

Age of the twinjet

As the world lurched from oil crisis to oil crisis throughout the 1970s and 1980s, fuel prices began to increase exponentially and Boeing's famed 747's economies of scale began to suffer. With four thirsty engines and an industry in dire straits, airlines began bleeding cash. Aircraft development soon began to focus more on fuel efficiency using smaller, more flexible-mission airliners and in the early 1980s Boeing arrived at a compelling dual-product solution. The 767 - a medium to long-haul widebody as comfortable plying its trade across the North Atlantic as it was flying from New York to Los Angeles; and the 757 - a narrow-body performance workhorse suitable for short-haul city hops and medium-haul cross-continent routes.

Despite its modest beginnings linking city pairs like London and Edinburgh, the 757 could be seen operating charter flights to the United States, either to Florida and the Caribbean (with a stop) from the UK or occasionally even on scheduled services (as BA once did, using it to link both Glasgow and Birmingham with New York JFK in the mid-1990s). As low-cost air travel began to take flight in the late 1990s in tandem with the tremendous improvement in living standards and the effects of globalisation, airlines began to explore new avenues for growth in the long-haul sector. With no dedicated airliner aimed at lower demand transatlantic routes, Continental Airlines (now United Airlines) turned to its existing fleet and began regularly scheduling its 757s between the east coast of the United States and western European cities. By offering onward connections through its Newark hub it could exploit the potential from smaller regional cities. Competitors soon followed suit. American Airlines, Delta Airlines, US Airways and Aer Lingus all began exploring the 757's inherent capabilities. And so, two decades after its first flight, the 757 found a new life as a transatlantic workhorse.

At this point you may be asking what is the relevance of this story to airport infrastructure and the rise of the A321 as a long-haul airliner? Much of the airfield pavements built in the seventies, eighties and nineties catered for a mixture of aircraft including the heavier 747s and DC-10s and the lighter, but more frequently used, 737s and A320-sized airliners. Comparatively speaking the 757 was a pavement engineer's (and consequently an airport's) most favoured of friends. Its main landing gear arrangement spread its modest take-off weights over a larger footprint than its short-haul stablemates. The stressing of taxiways and runways over their design lives was less than that of an A320 or 737. Its Aircraft Classification Number (ACN), a measure of the aircraft's pavement loading, is less than either of the latter airliners at maximum take-off weights (MTOW). From an engineering and maintenance perspective, the growth in the use of the 757 was airport-friendly and largely inconsequential to the upkeep and repair of airfield assets.

Rebirth of the A321

The 757 however, is nearing the end of its useful life nearly forty years since it first flew. Its once stellar cost per air-seat-mile is being challenged by the latest generation of Airbus and Boeing narrow-body aircraft. Until recently the 737 MAX was becoming a regular sight on the North Atlantic while Airbus continues to stretch the performance of its A321 - an aircraft which first flew in 1993. Indeed, the A321 is witnessing its own mid-life renaissance with the extended range 'LR' and 'XLR' models challenging the 757's territory. These points are significant. As transatlantic and long-haul travel continues to grow airlines such as Norwegian (737 Max), Aer Lingus (A321LR) and JetBlue (A321LR) are either already in, or will soon enter, this market with these aircraft. Others will follow suit. With over 2700 of all A321neo models on order, its popularity is increasing and its presence will become all the more common across western Europe and the eastern United States. To put those numbers into context, the current model A321 took over 25 years to accumulate its order tally of nearly 1800 aircraft while the A321neo has accumulated its current total in less than a decade.

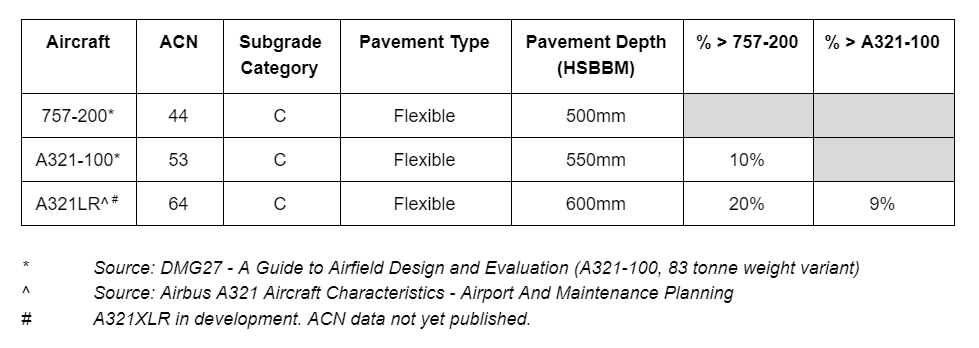

But while the 757's expansion in mission capability was largely subsumed by existing infrastructure, the same might not be said for the increasing number of A321s and its newer, heavier variants. When the A321-100 debuted in the mid-1990s it was available at an entry-level weight of just over 78 tonnes. By the time the A321XLR arrives in 2023 with a maximum take-off weight of 101 tonnes, this will represent an increase of nearly 30% over the original model. To put this into perspective, the table below shows example pavement design figures using 'DMG27 - A Guide to Airfield Design and Evaluation' with medium coverages on a high-strength bound base material (HSBBM). If the A321LR and XLR replaces the 757 and its mission capability on a like-for-like basis (and then factoring for growth in the medium term), it may not be unreasonable to see airports unexpectedly spending more money on both repairing and maintaining their pavement assets.

Posted: 2020-04-18 at 10:38 GMT